A lot has happened around the world in the past thirty months. A global pandemic forced everyone to stay indoors and download TikTok, the murder of one black man sparked protests in three continents, people hoarded toilet paper and noodles, and youths in the world’s most populous black nation were shot for daring to speak against police brutality. The world has also witnessed a (failed) attempt to overrun the White House, a despotic president’s nine-month ban on Twitter in his country, and the demise of a long-reigning monarch.

Deji Ajibade, Nigerian writer, psychologist and finance expert, plunges into his second body of work with the eagerness of an observer willing to make an elaborate commentary on the bizarre state of the world. The graduate of Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU) made his first foray into publishing via a self-help book, but this time he expresses himself in (free) verse.

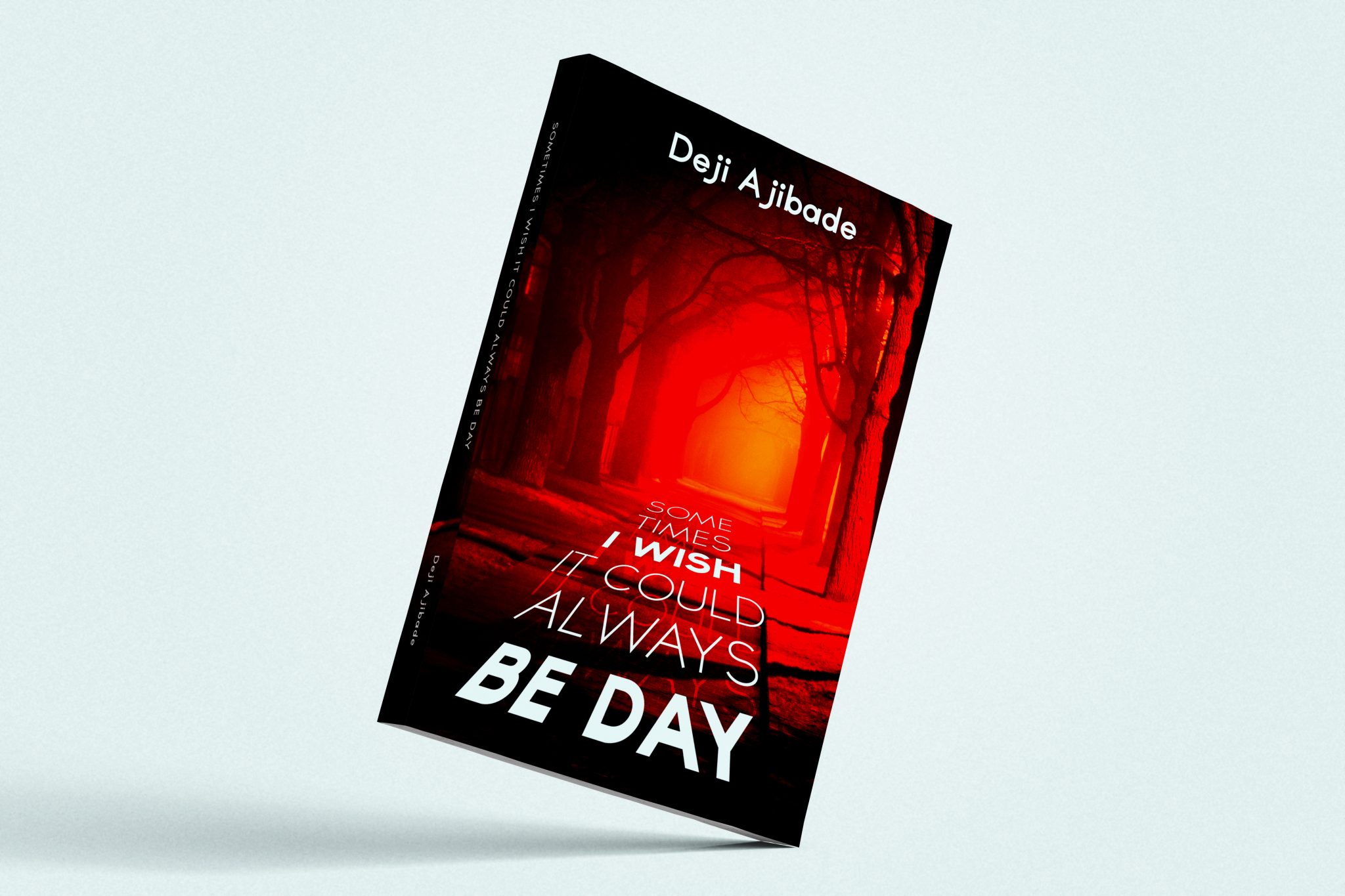

Sometimes I Wish It Could Always Be Day, a collection of 31 socially conscious poems, gets off to a flyer with “Children of Dust and Dirt”, a piece that seems to pay homage to David Diop’s “Africa My Africa”, but woven with threads of modernity. The poem seeks to exhort black people around the planet, urging them to be proud of the melanin that they’ve been blessed with.

Ajibade goes green in “Magic of Transformation”, where he wails about global warming and man’s tendency to exploit natural resources with no plans (or even intentions) to replenish. “Grief” dwells on the suffocating nature of sadness, and in the book’s title poem, he clutches tightly to memories of a deceased brother and father.

“for, in the depths of the night/my dreams carry me to dark places/ravaged cities that echo with grief/and hasty departures…”

Black people have somehow always found themselves dragged into war, even when they have no dog in the fight. This is the crux of the matter in “Even in War, There Is Hierarchy”, where Ajibade draws two allusions, one historic and the other modern. With respect to the first, his verses narrate how black people were conscripted into armies during the Second World War, and were not granted due honours even after risking their lives. For the second, he draws attention to the war in Ukraine, and how African refugees were ill-treated during the evacuation process.

“My Son” is a huge nod to the biblical injunctions in Proverbs Chapter 7, where the sage admonishes his son to embrace sexual purity. Anxiety dominates the discourse in the poem “In the Belly of Woeful Nights”, a thief’s immoral beginnings are illustrated in “Superman”, suicidal thoughts float around the room in “There Are Nights”, and modern variants of systemic racism are brought to the fore in “Like 2020.”

Hope is the anthem of the poem “Metamorphosis”, where Ajibade expresses the (faint) hope that Nigeria will somehow recover from its present socioeconomic woes and “take its rightful place” in global affairs. Social crusades segue into romantic affirmations in the saccharine “Tapestry”, which runs like the bridge of a 1990s RnB song.

“What holds the heart from falling into brokenness/like streaks of tears?/ Or, what propels its flight in smiles/if not love?/ your personality propels the flight of smiles across my face…”

Ajibade is not shy about his Christian leanings, and this reflects in several poems, as some verses begin to assume the shape of Old Testament psalms. Here, there is an emphasis on content rather than style or fluidity, but the message in this book is nonetheless passed in all its clearness.

To reference Nigerian pop singer, Tems, “Crazy Tings” have surely been happening since the turn of the decade, but there’s still a lot to hold on to, and the candle that is hope must not be allowed to flicker out. At least, that’s what Ajibade appears to be saying in this sometimes supplicatory, sometimes rueful, sometimes quizzical poetry collection.

(Sometimes I Wish It Could Always Be Day, published in 2022 under The Roaring Lion Newcastle imprint, is available in electronic format on Okadabooks, and in print at selected bookstores in the United Kingdom.)

About The Reviewer:

Jerry Chiemeke is a widely published writer, editor, music journalist, film critic and lawyer.

His short stories and essays have appeared in The Inlandia Journal, The Johannesburg Review of Books, The Guardian, The Republic, Bone and Ink Press and Agbowo, among others. He lives in Lagos, Nigeria, from where he writes opinion editorials and critiques of Nollywood films, African literature, and Nigerian music. Jerry is the winner of the 2017 Ken Saro Wiwa Prize for Reviews, and he was shortlisted for the 2019 Diana Woods Memorial Award for Creative Nonfiction. In 2020, he published “Dreaming Of Ways To Understand You”, a collection of short stories. In 2021, he covered the 10th edition of the Blackstar International Film Festival in Philadelphia as a film journalist.

Jerry has been a featured contributor FOR platforms like Okadabooks, BellaNaija, The Bagus, Netng, The Lagos Review, and the Opera News Hub. He has also facilitated writing workshops in different parts of Nigeria, and for his contribution to the Nigerian literary community, he was presented with the 2019 Connect Nigeria Award for Excellence. In 2020 and 2021, he facilitated the SprinNG Writers Fellowship as one of its mentors.